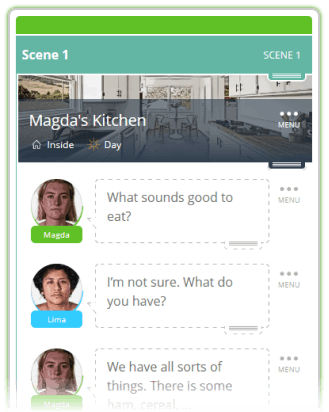

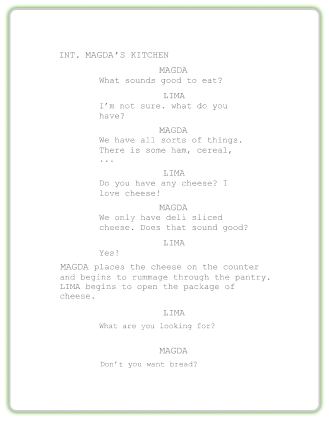

With one click

Export a perfectly formatted traditional script.

Export a perfectly formatted traditional script.

In our last blog post, we introduced the 3 main types of phone calls that you may encounter in a screenplay:

Only one character is seen and heard.

Both characters are heard, but only one is seen.

Both characters are heard and seen.

For a phone conversation where both characters are heard, but only one of them is visible to the audience, include the character extension for voice-over ("V.O.") for the character that is not seen.

A writer may choose not to show the second character for a variety of reasons. Two common reasons are 1) the writer is more interested in showing the actions and reactions of the on-screen character or 2) the writer wants to keep the identity or actions of the character on the other end of the call hidden from the audience.

JOHNATHON nervously pulls his cell phone out of his pocket and dials SHELLY. The phone rings.

Hello?

Hey, Shelly! It's Johnathon. How's it going?

Hey, Johnathon. I'm so glad you called. Everything is good here. I just got home from work.

How about that for timing? Hey, so I was wondering if you might like to grab a cup of coffee sometime?

I would absolutely love to!

You would? Great! How about Friday at 10?

For this scenario, use the voice-over character extension ("V.O.") for the unseen character, as shown above for Shelly's dialogue. The application of the character extension for voice-over is often confused with the extension for off-screen ("O.S"). The difference between the two lies in the location of the unseen character. You will almost always use "voice-over" for this type of phone conversation.

The character speaking is not in the same location as the character that is visible to the audience.The example above demonstrates this application. Since Shelly is not anywhere in Johnathon's apartment, we use "V.O."

The character speaking is in the same location as the visible character.This extension would be used if Shelly and Johnathon were not on the phone, but rather talking to each other from different parts of Johnathon's apartment (i.e. Shelly talks to Johnathon from the kitchen, while the audience sees Johnathon's reaction and reply on-screen from his bedroom).

Writers may select the voice-over phone call scenario in their screenplay for a variety of reasons including:

The writer is more interested in showing the actions and reactions of the on-screen character.

The example in the infographic above demonstrates this use of the voice-over tool. The writer wants the audience to focus on Johnathon and his reaction to Shelly's acceptance of his date proposal.

The writer wants to keep the identity, location, and/or actions of the character on the other end of the phone call hidden from the audience.

One well-known example of this use of the voice-over tool is the phone conversation between Bryan Mills and Marko from the 2008 action thriller, Taken, right after Bryan discovers his daughter has been kidnapped.

(into phone)

I don't know who you are. I don't know what you want. If you are looking for ransom, I can tell you I don't have any money. But what I do have is a particular set of skills; skills I have acquired over a very long career. Skills that make a nightmare for people like you. If you let my daughter go now, that'll be the end of it. I will not look for you, I will not pursue you. But if you don't, I will look for you, I will find you, and I will kill you.

Good luck.

(Dialogue by Taken screenwriters, Luc Besson and Robert Mark Kamen.)

In this example, the writers hide Marko, the kidnapper's, location and reaction to Bryan's statement from the audience to add to the suspense of the story.

Be sure to check in for our final post on this "How To" topic later this week.

Like this article? Share it on social media using one of the links below!

Thanks for reading, writers! Until next time.