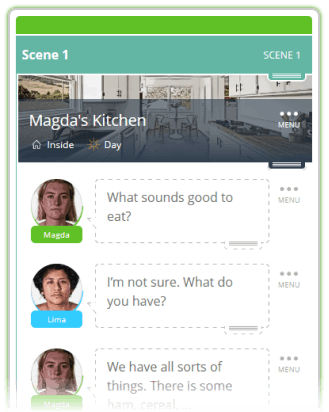

With one click

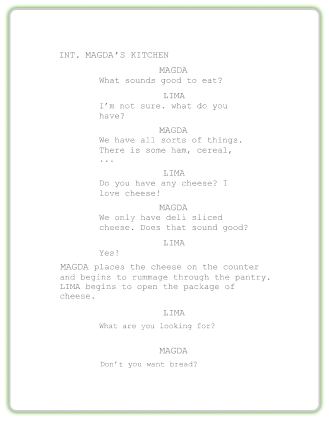

Export a perfectly formatted traditional script.

There are some key differences in writing a screenplay versus writing just about anything else. For starters, that dang formatting structure is very specific, and you won't get far (at least, for now) without knowing it. Screenplays are also meant to be blueprints for, ultimately, a visual piece of art. Scripts require collaboration. Multiple people need to work together to create the end story which plays out on screen. And that means that your screenplay needs to have a compelling plot and theme and lead with visuals. Sound hard? It's different than writing a novel or poem, but we have some pointers to help you learn the visual storytelling skills you'll need to write a script.

Export a perfectly formatted traditional script.

Learning to tell a story visually is one of the essential pieces of advice that screenwriter Ross Brown hands down to his students at Chapman University, where he's the chair of the creative writing MFA program. Brown spent years writing for television, including the popular U.S. shows such as "Step by Step," "The Facts of Life," and "Who's the Boss?" among other producer and assistant director credits. He recommends that his students start on their screenwriting journey slowly – at least when it comes to the length of script you're going to tackle.

"So, what advice would I give to someone who decides that they want to start to learn how to be a screenwriter? … Write a short film first," Brown advised. "If somebody were going to learn how to write a novel, they'd probably tackle a short story first—the same thing with screenplays. Try a ten-minute film first. Make some mistakes. Learn from them. And then try something a little bit longer, and then maybe the third time try a feature-length."

He also recommends his students do a lot of reading to understand what makes a script work from the page to the screen.

"You should read some screenplays because it's very different to read a screenplay than to watch a movie," he said. "Learn how screenplays look on a page and are laid out, and how to communicate in visual language."

Visuals are what capture an audience. It's what makes film and television different from any other storytelling medium. So, how do you communicate visually in your screenplay when all you have to work with are words?

Incorporate visuals in your screenplay in these specific places:

Location description

Character description

Character action

Scene action

Location descriptions or setting descriptions will be used almost every time you start a new scene, but these visual cues are vital in your opening hook. A screenplay's opening hook is what draws the viewer in, makes them curious, and sets the tone for the rest of the film. Your scene should occur in a particular place for a reason, though, so don't just make it sound cool for cool-ness' sake. What does the location do to raise the stakes? Does it give obstacles to the characters? In David Trottier's book "The Screenwriter's Bible," he uses the following screenplays as excellent examples of location descriptions that hook the viewer.

Please note: Screenplays mentioned in the following examples are used for educational purposes only.

Notice how screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan expertly uses visuals and sound and explains where the viewer is witnessing this scene from in his screenplay for "Body Heat."

Flames in the night sky. Distant SIRENS. PULLING BACK, we see that the burning building is mostly hidden by dense, black shapes that define the oceanside skyline of Miranda Beach, Florida. We're watching from across town. The sound of a bathroom SHOWER comes to a dripping stop at about the same time we see the naked back and head of NED RACINE. We continue to PULL BACK INTO –

Racine, dressed in undershorts, is standing on the small porch off his apartment on the upper floor of an old house. Racine lights a cigarette and continues to stare off at the fire. We've passed him now, into the bedroom of the apartment, and the shape of a young woman, ANGELA, flashes by, drying her body with a towel.

Now watch this scene:

In "Apocalypse Now," the setting description quickly transports the viewer to a ghostly war zone, and the opening scene in the movie matches it almost exactly as the viewer would picture it by reading the screenplay.

Coconut trees being VIEWED through the veil of time or a dream. Occasionally colored smoke wafts through the FRAME, yellow and then violet. MUSIC begins quietly, suggestive of 1968-69. Perhaps "The End" by the Doors. Now MOVING through the FRAME are skids of helicopters, not that we could make them out as that though; rather, hard shapes that glide by at random. Then a phantom helicopter in FULL VIEW floats by the trees-suddenly without warning, the jungle BURSTS into a bright red-orange glob of napalm flame.

The VIEW MOVES ACROSS the burning trees as the smoke ghostly helicopters come and go.

DISSOLVE TO:

A CLOSE SHOT, upside down of the stubble-covered face of a young man. His EYES OPEN...this is B.L. WILLARD. Intense and dissipated. The CAMERA MOVES around to a side view as he continues to look up at a ROTATING FAN on the ceiling.

Now watch this scene:

Character descriptions appear when a character is first introduced in your screenplay, and character action follows subsequent scenes. When we first meet your character, you have a chance to tell us something about them in a few words that describe their physical appearance and their personality. Make sure to avoid too much description that can't appear on the screen. Everything you write should be translatable visually. Character descriptions should be no longer than a sentence (although some exceptions apply), and character action should always move the story along somehow.

In this example from "The Shawshank Redemption," notice how the character description tells you something about the warden's appearance and personality by using visual cues, but it does not detail his height, weight, and hair color.

WARDEN SAMUEL NORTON strolls forth, a colorless man in a gray suit and a church pin in his lapel. He looks like he could piss ice water.

Character action tells us what the character is doing in the scene, either while dialogue takes place or in silence. How are they moving about their space?

In this example of character action below from "A Quiet Place," we're watching the cautious movements of a woman who is scared to death to make a noise. Sound heightens the tension. This film is entirely made up of location description and character action, as it features no dialogue. It's an excellent read if you're trying to learn to write visually.

ON THE MOTHER... as she inhales slowly? And then, as if doing surgery, she slowly closes her hand around the bottle and GENTLY begins to move it through the shelf toward her. Her hand, once again moves incredibly slowly, her now wider closed hand shifts even more bottles as it passes. JUST as she gets to the end of the shelf a bottle shifts... with a RATTLE of pills. This is the first, deliberate sound we've heard. The mother... FREEZES!!!!

What's happening around your characters that adds to their milieu? Perhaps there's a semi-truck swerving dangerously close to the character's car, a helicopter buzzing overhead, or a loud parade adding chaos to a chase. Things that happen around a character can heighten the tension and raise the stakes, but visuals are key here. Give the reader a sense of what it feels like to be in the middle of what's happening. Without adding director cues, you can still "direct" the scene, if you will, by describing precisely what action the viewer would be witnessing, beat by beat.

In this example of scene action from "The King's Speech," it is not what the character is doing but what's happening around him that heightens the tension.

The red light in the booth flashes.

The red light flashes for the second time.

Bertie concentrates.

The red light flashes for the third time.

The red light now goes steady red.

Lionel opens his arms wide and mouths, "Breathe!".

On Air.

Bertie's hands begin to shake, the pages of his speech rattle like dry leaves, his throat muscles constrict, the Adam's apple bulges, his lips tighten...all the old symptoms reappear.

Several seconds have elapsed. It seems like an eternity.

Can you write your script with just visuals? It's an excellent exercise to go through to see where you can cut down on dialogue and do more showing than telling. Don't make a character say something if they can show it instead. Take this passage from Trottier's "Bible," for example:

"Do you recall the barn-raising scene in "Witness"? When the workers pause for lunch, the eyes of the elders are on Rachel Lapp, who is expected to marry an Amish man but who likes John Book. Without a word of dialogue, she makes her choice by pouring water for John Book first."

Incorporate action into dialogue – what is the character doing while they're talking?

Incorporate barriers for your characters, whether physical or internal barriers that we can see externally. Perhaps a loud noise in the background makes it harder for your character to explain to someone how to dismantle the bomb, or excessive heat makes your character visibly anxious during an already tense moment.

Use descriptive verbs that more accurately describe the action. Instead of a man "walking" into a store, perhaps we learn something about his personality because he instead "saunters" into the store. A semi-truck that "drives by" is different than a semi-truck that "barrels down the road."

Remove all passive language, and make sure the action is happening in the here and now.

Remove direction both for the director and the actor, for example, "We pan to …," "The camera angles on …," or "She raises her eyebrows in surprise."

Remember that your writing shows the reader what they would see on screen because they can't actually see it just yet; you're not just telling an audible story. If you had to paint the scene, what would we see happening?

Paint me a picture,