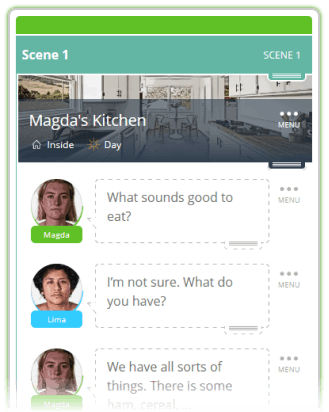

With one click

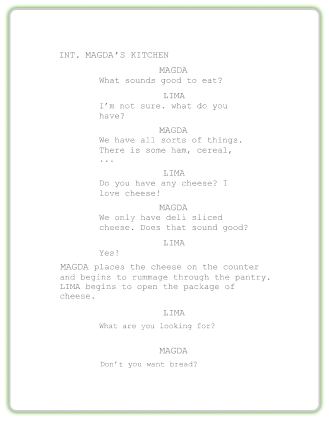

Export a perfectly formatted traditional script.

A myth is a story based on tradition that helps us better explain our world and the human condition. Until the late Joseph Campbell came around, Hollywood may not have known that its stories on the silver screen were based on ancient myth. But today, storytellers around the world recognize that there is a pattern in most great stories, whether they play out on stage, in a soap opera, or as a blockbuster superhero film. You, too, can use this mythic pattern to your advantage.

You’re likely already incorporating some mythic structures into your stories and characters without knowing it. That’s how deeply mythological stories are ingrained in how we view the world. Once you get a solid grasp on the regarded mythic archetypes, you can leverage them to make your characters and their journeys even more compelling.

Export a perfectly formatted traditional script.

We interviewed author and screenwriter Phil Cousineau on the topic since he literally wrote the book – or at least one of them - alongside Campbell in 1990. In “The Hero’s Journey: Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work,” Campbell recounts his own mythological quest. Cousineau also has more than 20 screenwriting credits to his name, including a co-writing credit on “The Hero’s Journey” documentary.

“One way to think about myth is that it’s a sacred story,” Cousineau began. “It’s a story that often an entire culture is based on.”

These stories and their unique characters hail from around the globe and across time: Think Greek gods, goddesses, and plenty of monsters, Celtic fairies and elves, Norse warrior gods, Eastern Europe’s witches and vampires, Far Eastern dragons, the cities of gold found in the Americas, and the underworld of Egypt. Though the terms vary slightly in meaning and style, folklore, legends, and fairytales can provide you with fantastic inspiration for the underpinnings of your next screenplay. After all, these stories have been told throughout time and around the world to help all of us “feel less alone,” Cousineau said.

Campbell coined the idea behind the word monomyth, which describes his theory that a typical pattern exists beneath the plots of all great stories, no matter the country or culture they come from. That monomyth is something we all experience in our lives, which is what makes stories based on this common structure so appealing and relevant to us. Generally, we (or your characters) set out on a path to change something, and certain things inevitably happen to us. We meet allies, overcome obstacles, encounter and face fear, and we all have to go through these stages to see our characters (or ourselves) evolve.

“Myth gives you the underpinnings. So, the underpinning is where all the meaning is,” Cousineau explained. “The overstory is the plot.”

Treat Campbell’s monomyth, or The Hero’s Journey, as the backbone of your screenplay.

This is the original world of the hero, where the hero lacks something or something is taken from them.

The hero is faced with a challenge or adventure, establishing their goal.

The hero is reluctant to heed the call but is eventually convinced by a higher calling or motivation.

The hero meets someone who gives them advice, but this person cannot go with the hero on their journey.

The hero commits to taking on the task and enters this new reality.

In this new reality, the hero learns the rules through several people who give them new information, and the hero begins to reveal his true characteristics.

The hero and his allies have reached a dangerous place where the purpose of the journey is hidden.

The hero faces a life or death situation, either physically or psychologically.

The hero survives and seizes the object of the quest.

The hero is faced with the consequences of their actions and the decision of whether or not to return to their old life.

The hero is faced with one final test before they can emerge in their new form.

The hero returns from their journey with their newfound treasure, love, freedom, or wisdom. If we’re dealing with a defeated hero, we see that they’re doomed to repeat their mistakes.

During this mythic journey, your hero will encounter other traditional archetypal characters, and you should also study these to use as references in your screenplay. Sure, they might look different and have different motivations. Still, Campbell argues that the people we encounter on our own journeys – and in the movies – fit pretty neatly into certain archetypes.

“One character from an ancient myth can be the face or the personification of an entire culture,” Cousineau explained. “If you think about old England, who comes to mind? King Arthur. You need a face to make some of the archetypal ideas come to life, come to power. So that’s all personified in one character.”

The hero leads the story. They’re flawed but admirable in some way, and they will undergo a transformation by the end of the journey. They willingly sacrifice their own needs for the needs of others.

This person will aid in the hero’s journey by teaching them something they need to know and protect them. The mentor prepares the hero for the journey ahead and often convinces them to go on it.

This character prevents anyone but the hero from entering into the new reality. They must be overcome, either by being passed in some way or by becoming an ally. They will test the hero’s commitment to the journey.

The herald motivates the hero to take action. This character also typically reveals the challenge.

This dark-side character or force reveals itself in the form of enemies and villains to challenge the hero. They must be a worthy opponent.

Tricksters often provide comic relief for the hero and the story but are also mischief-makers. They want to create change, and they often point out or help reveal the character’s flaws.

The shapeshifter is often the opposite sex of the hero and serves as an unstable force that creates tension and doubt.

Of course, certain myths offer more specific structures and archetypes, and you can use these as starting points to create stories that will resonate with people of all cultures and backgrounds. Your characters don’t have to follow the structure exactly – in fact, to keep things interesting, let them veer off the path or meet someone with a different archetype every once in a while. Maybe they meet someone who embodies multiple archetypes, for example.

There are plenty of resources out there to study the great myths, including “The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers” by Christopher Vogler and one of my personal favorites, Mythology – a Spotify Original podcast.

“You’re in mythic territory, and that’s what gives [your story] this hum,” Cousineau concluded. “It gives emotion, it gives a sense of mystery, and it gives a sense of one story that’s being told again, and again, and again throughout time.”

We’ve heard it all before,