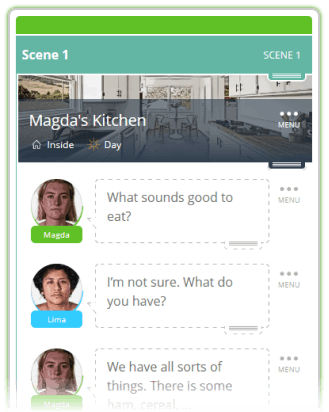

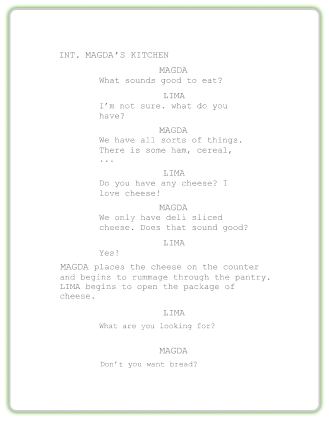

With one click

Export a perfectly formatted traditional script.

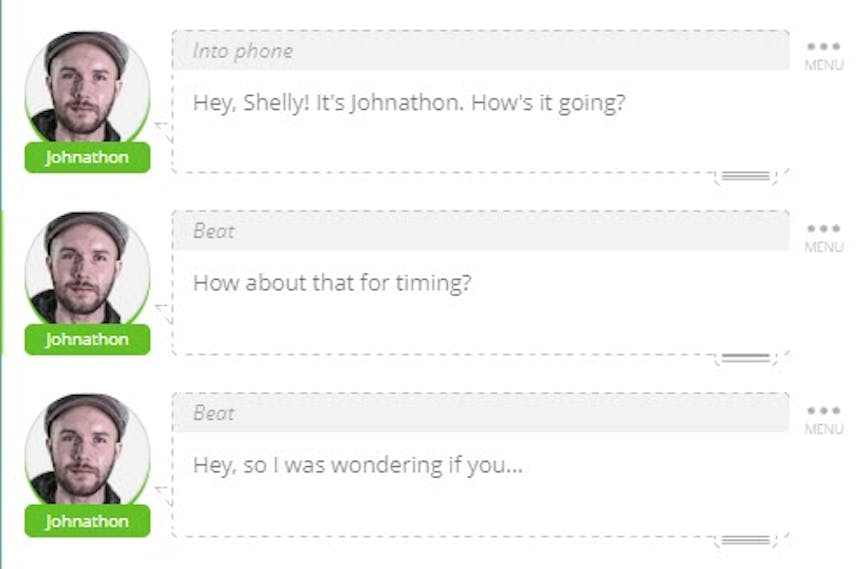

While screenplays don’t have to include a ton of dialogue (or any dialogue for that matter), most screenwriters do lean on dialogue to help move their story along. Dialogue is any spoken words or conversation among characters in your script. It sounds realistic, but when you dig a little deeper, it probably doesn’t mimic precisely how we talk because, in a screenplay, dialogue must have a focused, quick purpose. There’s no rambling in a screenplay; in the best scripts, the dialogue gets to the point.

There are some simple rules for writing strong dialogue in your story and some big-time no-no’s. I found that one of the most valuable guides to writing dialogue describes what NOT to do, though. The 7 Deadly Dialogue Sins, as explained by David Trottier in The Screenwriter’s Bible, gets to the heart of things: Remove blatant exposition, don’t overwrite, don’t exaggerate character emotions, just say no to everyday pleasantries, stop repeating information, leave room for subtext, and avoid cliches.

Export a perfectly formatted traditional script.

“Movie dialogue should snap, crackle, and pop,” Trottier says.

Snap is the crispness, crackle is the freshness, and pop is the subtext. Crisp dialogue is short and to the point. Fresh dialogue is original.

“The subtext pops when the text snaps and crackles,” he continued.

As in, it’s not what you say but how you say it.

If you don’t already own Trottier’s Bible, I highly recommend you secure a copy if you can. He explains writing lessons in a way that clicked with me. So today, I’ll share those 7 Deadly Dialogue Sins with you in more detail and give you the bonus of examples. Everyone loves an example, am I right?

Your characters should never tell each other something that they already know or that the audience already knows, for that matter. Make sure your characters speak to each other, not the viewer, to keep obvious exposition out of your story. The audience does not need to know everything all at once. This is often called “on-the-nose” dialogue. It occurs when a character speaks exactly what they’re thinking or precisely what the audience needs to know for the story to move forward without any subtlety. It’s the line that says, “Oh no! There he is!” when we see him right there. Remember what your audience is viewing because it probably doesn’t need to be said if they can see it.

I am really sorry to hear that your friend died last night, Jerry.

I am really sad. He was killed in a freak car accident.

Both of these lines could be shown rather than told. Perhaps Sarah gives Jerry and side hug and says, “hang in there,” while Jerry stares up at a crucifix in church, pondering the brevity of life. Okay, this is getting dark. Let’s move along. You get the point!

Don’t use more words to say something than are necessary. It slows down your script, and eventually, your actors. It also bores your audience to tears. You never want a viewer to be saying, “get on with it, already” in their head. Today, junior! Specifically, Trottier cautions to avoid question and answer sessions, police interrogations, and speech-making scenes. Allow characters to interact with each other and interrupt, similar to a normal conversation. Limit longer sections of dialogue to one idea. Watch out for overwriting in your scene and action descriptions, as well.

When she walks into the room, everyone else disappears. I am obsessed with her.

Hey Bart! We know you’re obsessed with her by your first sentence—no need for the overwriting in the second.

If you’re adding exaggerative punctuation to your characters’ dialogue or parenthesis to indicate (yelling), (whispering), and the like, it’s a pretty good sign that your characters suffer from a lack of either context, motivation, or clarity. If your characters are as strong as they should be, there is no question about the tone of their dialogue – your reader should already know how they’re going to deliver a line. Less is more.

(sobbing)

O-M-G. How could you do this to me?!

(eyes roll)

You are so dramatic.

Knowing Kelly to be a very dramatic, over-emotional sorority sister and Sybil to be the motherly one of the friend group (which we learned earlier in their hypothetical character descriptions), neither parenthesis comment is necessary. The exclamation mark is probably unnecessary as well because we already know how Kelly would pose a dramatic question.

Get into and out of a scene as fast as possible. Have you ever seen a great movie scene that starts with, “Hey, how are you today, Sally? I’m great, Bill, thank you for asking. And your kids – how are they?” Name one; I’ll wait. … … …

Introductions, small talk, and chit-chat are as dull in a screenplay as they are in real life.

Hey, do you remember me? I’m Roy from accounting.

Oh, hey Roy. I do remember. How’s that cute dog of yours?

You remembered! He is doing well. And your cat?

I’ll stop there because I can’t take anymore!

If the audience already learned something in a previous scene, there’s rarely a need to repeat it through dialogue in a later scene. Take this example of action description in one scene, followed by dialogue in the next.

Steve struggles to gain control of his frozen fingers, nearly misses the detonation button, and clips the line to dismantle the bomb.

Well, Steve, you did it. You dismantled the bomb.

This one is pretty self-explanatory.

Let your characters imply what they mean by leaving room for subtext, which is said through the situation, body language, attitude, metaphor, and double entendre. The subtext is what is left UNSAID.

My shirt is ruined!

A little Tide and hot water should do the trick.

Lamarr throws his ruined shirt into the basket of dirty laundry. Betty, peeved, looks up from scrubbing the floor nearby.

Okay, I guess I’ll take care of that.

Betty says she’ll take care of treating the stain on the shirt even after instructing Lamarr how to do it, but what she’s really saying here is she feels like the only one who does the chores around the house. That is subtext.

To demonstrate, here’s a list of cliché phrases and dialogue derived from other movies that NO ONE wants to hear in your screenplay. If you have a good reason, then go for it, but don’t say I didn’t warn you.

We’re not in Kansas anymore.

There’s no place like home.

Show me the money.

I’m the king of the world!

We can do this easy way or the hard way.

I’ll be back.

Hasta la vista, baby.

Shaken, not stirred.

Here’s looking at you, kid.

You’re going to need a bigger boat.

If you build it, they will come.

Just keep swimming.

Are you talking to me?

As if!

I’ll have what she’s having.

Nobody puts Baby in a corner.

Snap out of it!

Houston, we have a problem.

You can’t handle the truth.

You had me at hello.

You’re killing me, smalls!

You better run!

It’s gonna blow!

We’ve got company.

They’re behind me, aren’t they?

Don’t die on me,

Get out of there!

Is that all you’ve got?

You’ll never get away with this! – Watch me.

How hard can it be?

I was born ready.

I’m just getting started.

Not on my watch!

Wait! I can explain.

Of course, the list above is not exhaustive. If your dialogue sounds like you’ve heard it before, you probably have. Write it in your own words! Originality is so hot right now (see what I did there).

So, are you a dialogue sinner or a saint? We can always improve, so I hope you’ll run your screenplay through these 7 Deadly Dialogue Sins to see where you can brush up, cut out, and cut down. If you want more help with writing dialogue that sings, head over to the Top 5 Tips for Writing Dialogue in a Screenplay by screenwriter Victoria Lucia. Keep practicing, and you’ll be making Aaron Sorkin proud in no time 😊

It’s not what I said, but how I said it,