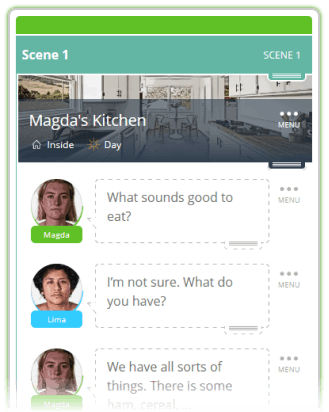

With one click

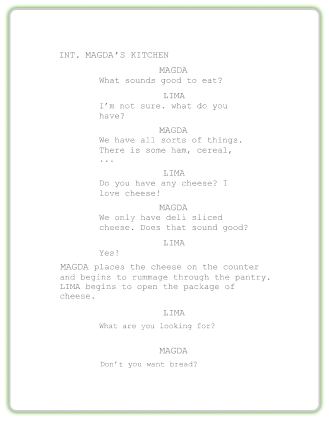

Export a perfectly formatted traditional script.

Even with excellent counsel on your side, it’s hard to know exactly what to look for in a screenplay purchase agreement or option agreement; option length, script credits, rights, and bonuses are big ones. But there are two other things to watch for when optioning or selling your screenplay: low-money option fees and reversion clauses.

We sat down with legal expert Sean Pope of Ramo Law, an entertainment attorney firm with offices in Beverly Hills and New York City. Besides pointing out two things to look out for when optioning or selling your screenplay, he explains why these items could spell trouble for you, the screenwriter, down the road.

Export a perfectly formatted traditional script.

In this article, learn more about low-money option fees and reversion clauses and how these may negatively impact the creator while benefitting the purchasing party.

One trap screenwriters often fall into is the low-money option. This is especially true for writers who have never optioned a script before and are simply excited at the prospect of possible production. While a low-money option is not a great deal in terms of payment, there’s an even worse reason why you may want to avoid this legal pitfall.

The second thing to look out for is the lack of a reversion clause. A producer or executive rarely offers this up in your purchase agreement, so you have to ask for it.

Below, Sean explains these two things to watch out for. While they appear simple on the surface, there could be a sneakier reason why you will or won’t find them in your screenplay legal agreement.

“I would say one that is not terrible, but it’s something that you kind of have to keep in mind when you’re doing these, is option deals that have an option fee for very little money up front,” Sean began. “like the option fee is $1, where you’re giving this production company the exclusive right to purchase the screenplay but they’re not having to pay for that exclusivity.”

When a company or producer options a screenplay, they’re essentially paying the screenwriter a fee to rent the script for a little while and see if they can drum up interest from a director, cast, and perhaps financiers. If they can’t, you get the script back. If they can, they’d get the right to purchase the screenplay.

These fees can range from $1 to thousands of dollars.

But in exchange for that fee and the opportunity to have your screenplay produced, you can’t shop it around to anyone else for the specified period of time.

“So, you’re blocked from doing anything with your screenplay for 18 months or approaching other production companies when they paid nothing upfront,” Sean said. “And that can be a really cheap option agreement, or sometimes it’s also called a shopping agreement where you’re granting them exclusivity for them to go out and take it to market, and they’re not having to put any skin in the game.”

If you’re sitting on a pile of great scripts, it might not make much difference to you to have one script out of commission for a while in exchange for the chance of having it produced. But if you only have a few viable scripts for the current market, you should ask for more cash for the option.

“So then, there’s kind of a common deal where, if you’re able to, you’re going to want to either negotiate a higher option fee or really evaluate if you want to work with that production company themselves,” Sean said. “They might have a very viable reason for doing that, or they might not, and they just want a deal with cheap exclusivity on that screenplay.”

“Another clause that typically will not come in a deal that you are going to have to specifically ask for is what we call a reversion clause,” Sean said.

In a screenplay purchase agreement without a reversion clause, the producer or company that bought your screenplay paid a specified purchase price to own all the rights to the script.

“A reversion clause says hey production company, even though you paid the purchase price, you have to go into production and use the screenplay within a negotiated amount of time, two to four years after you pay the purchase price. Otherwise, the rights to the screenplay revert back to me, the writer, and I get to take them elsewhere,” Sean explained. “That’s to prevent a production company that might have many, many scripts or a studio that might have a bunch of scripts, and they’re really purchasing yours cheaply because they have another screenplay that they really like, which is very similar in scope and they don’t want someone else producing it. So they’re telling you they’re going to produce it, and they pay the purchase price, and then it sits on the shelf for 40, 50 years, and you have no ability to ever exploit that as the writer.”

You’ve heard of the screenwriters who’ve sold tons of scripts during their lifetime but have yet to see a “written by” credit on a film? While the scenario above is not always to blame, Sean said, “it can be more common than you think.”

“So something you might want to ask for is that reversion clause in order for those rights to revert back to you at the end of the day if they’re not making any steps to progress to production,” Sean said.

An initial agreement won’t typically feature a reversion clause because it’s not beneficial to the purchasing party.

“It’s something you as the writer are going to have to actually ask for,” Sean said.

Understanding what to look for in a screenplay option or script purchase agreement will help you protect yourself and your life’s work when the opportunity knocks. While producers and production companies aren’t always trying to be sneaky, they will always do what’s best for them unless you know to ask otherwise.

Did you enjoy this blog post? Sharing is caring! We'd SO appreciate a share on your social platform of choice.

Make sure your legal agreements are fair by considering the option price and asking for a reversion clause in the event that someone wants to buy your screenplay.

I’m just taking a vested interest in you, writer,