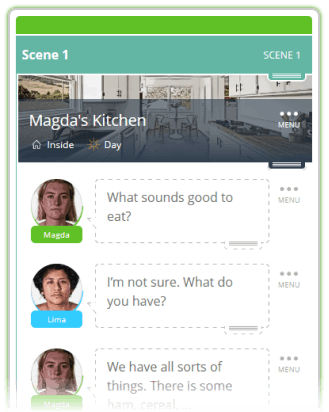

With one click

Export a perfectly formatted traditional script.

If you thought live-action screenwriting was heavy on the visuals, wait until you see what a screenplay written for animation looks like! I'd consider animation an entirely different medium for storytelling, though some call animation a genre. Today we're exploring how to write for animation, whether that's an animated television show or a movie, and how the process differs from traditional screenwriting.

Export a perfectly formatted traditional script.

To start, we interviewed former Disney Animation Television writer Ricky Roxburgh (now at Dreamworks as a story editor). As a staff writer, he's written episodes of some of your kids' favorite animated television shows, including "Rapunzel's Tangled Adventure," "The Wonderful World of Mickey Mouse," and "Big Hero 6: The Series."

There are many similarities between a screenplay written for animation and a screenplay written for live action, but the production process is much different. It varies again if the script is written on spec for a feature or by staff writers on an existing show.

"What is different is the script's path to the screen," Roxburgh began. "If you're working in feature, the scenes are often rewritten over and over and over and over and over with the story artists. If you're in TV, you may be writing an outline, like when I do the "Mickey Shorts."

According to Animation Screenwriter Jeffrey Scott, author of "How to Write for Animation," these are the key differences between an animated screenplay and a live-action screenplay:

A screenwriter almost has a chance to "direct" when writing an animated script because the writer needs to be incredibly detailed about everything that the viewer will see (and the animator will draw). This is different from live action, where the screenwriter should write visually and leave some of the direction open for interpretation when the director comes on board. In live action, noting camera direction for the director is usually a no-no.

Due to the amount of description, a single page in an animated screenplay equals about 40 seconds of screen time. In contrast, a single page in a live-action screenplay correlates to approximately one minute of screen time.

Unless you're writing a spec script for an animated feature and trying to convince someone to produce it later, you're likely going to be a staff writer who a studio hires to write either a feature or television show. You will work with several people in this process, not limited to other writers and story artists. Your script will change many, many, many times, so you have to be willing to be part of the shaping and molding process until your team reaches its final product. "Going back to the drawing board" gets an entirely new meaning.

While there are exceptions, animated movies and television are usually centered on family-friendly stories based on fantasy, science fiction, moral themes, and some anthropomorphic characters. The stories are animated because they have to be animated (unless you have a huge special effects budget to make a candlestick sing!). They make more sense as an animated story than as a live-action production. Animated stories also often feature music and singing that can better hold a child's attention.

In the early days, writing for animation wasn't writing at all, but instead a collaboration among story artists who discussed a storyline ahead of time, then broke out on their own to animate their assigned sequences. It's why you'll see many story artists on early animated Disney films with writing credits. Later, story artists might storyboard ahead of time, with the left-hand column of a sheet of paper featuring story beats and the right-hand column featuring quick sketches to match. Once studios began outsourcing animation, writers who didn't animate had to come in to spell out what was expected in the drawings, making animation scripts a requirement. Today, animation writers have to be incredibly descriptive to give direction to the artists about precisely what should appear on the screen.

Animation writers also collaborate heavily on their projects, and a script is never done until the animation is also. Of course, it varies from television show to television show, as Roxburgh pointed out to us. Sometimes, you'll hand off a script to animation, and they'll make any changes as necessary. But sometimes, that script comes back to you, the writer.

"If you're in TV, you may be writing an outline, like when I do the "Mickey Shorts." I write an outline, and that goes through story artists, and the story artist fleshes these scenes out," he said.

On "Rapunzel's Tangled Adventure," more collaboration is required.

"If I'm writing "Tangled," those scenes are written, and then the story artist may embellish certain things, and then I might have to come back, and so it's a slower process, and it's almost like micromanaging the actors, in a sense, or the performances, because you know animators and story artists are doing that. So that process is a little bit different."

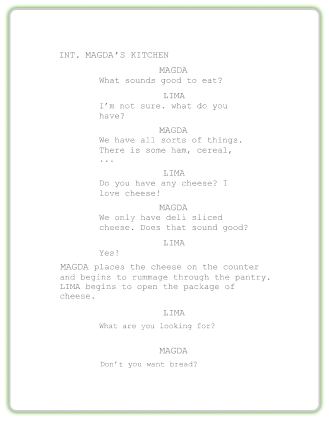

There are also two different kinds of screenplays that you'll generally see when you look at animated feature or television show scripts. One reads just like a traditional screenplay, and you might see this used on a 3D film. The other, used more frequently on 2D films and TV shows, will include camera movements and more director-like descriptions.

Take this example from the animated television series "The Fairly Odd Parents." Steve Marmel and Mike Bell wrote this episode. The writers are particular about everything that needs to be illustrated, but we don't see the specific camera shots noted.

A PIRATES-OF-THE-CARRIBEAN-LIKE TOUR BOAT bobs on STOMACH ACID. The passengers include a STOMACH FLU COUPLE and a MALE PARASITE, in a white leisure suit, who sits alone. A TOUR GUIDE –- a 16 year human old kid – sits at the front in a safari suit.

We still have room for one more pair of germs for our journey through the inside of an evil girl! Anybody? Going once… going twice…

You can read the entire script and many other episodes of this popular animated show by visiting executive producer Fred Seibert's Scribd profile. He also makes storyboards, pitch decks, and bibles available for your viewing pleasure! Lots of good stuff there.

Here's another example from a later draft of the "South Park" movie, written by Trey Parker, Matt Stone, and Pam Brady. In it, you'll find director-like cues and precise angles.

Good morning South Park! It's five-thirty a.m. on Sunday!! Time to feed the horses and water the cows!!

From the back, we see the blond haired kid sit up from his bed. He stretches, and then walks over to his closet.

We still only see the boy from the back as he reaches in his closet and pulls out an orange coat.

The kid puts his coat on, then turns to camera and pulls the hood shut, so that we never get a good look at his face.

And later in the same script …

CLOSE UP on a bag that reads 'CHEESY POOFS'. A hand reaches into the bag, pulls out a wad of orange crunchies and raises them --

BOOM UP to reveal the fat face of eight year old ERIC CARTMAN who chows down on the chips.

Now we see that fat little Eric is sitting on his couch, eating Cheesy Poofs and watching television.

The doorbell rings. Cartman doesn't move a muscle.

MOM! SOMEBODY'S AT THE DOOR!

Do you have a favorite animated television show or movie? Here's an exercise: Watch it again, keeping in mind what you learned about how to write an animated screenplay above, then try your hand at transcribing it. You'll learn just how specific you need to be in your scene and character descriptions.

In short, yes – writing for animation is different than writing for live-action, but the need for a great story exists no matter the medium. Flashy animation and crazy characters and locales won't make up for a boring story with no theme or lesson. However, writing for animation can be a ton of fun because there are no limits to what your characters can do and where their stories can exist.

Let your imagination run wild!